Roundtable

The conference was closed by a plenary discussion that was entitled “whither politicisation?” (See also the disscussion in the volume “Rethinking Politicisation in Politics, Sociology and International Relations”). The aim of the roundtable was to discuss politicisation and its relation to EU integration: Could politicisation be a remedy or would it rather increase the various crises we have seen within the EU context?

The debate is ongoing, discussed in further research projects:

Jean Monnet Chair · DebatEU

Claudia Wiesner shortly wrapped up the conference discussion. She said that the participants had heard about different challenges the EU and democracy are facing in these days and argued that theses challenges are interrelated: the actions of the European Central Bank during the sovereign debt crisis for instance, are related to an increase of populism.

Moreover she resumed that the conference had not only been discussing the EU, but also representative democracy in a larger perspective. Most speakers agreed that crisis talk is omnipresent yet often not adequate, as the challenges or problems the EU faces are not necessarily a crisis, but rather critical moments. It is not that life and death of the European Union is at stake. However, the presentations indicated a number of problem fields and a number of sources of democratic deconsolidation, growing inequality, the downsides of economic liberalism, populist protest, problems of representative democracy and participation. All of these phenomena are interrelated facets of what is discussed as “the EU´s crisis”. Moreover, the EU as such furthers on the one hand de-democratisation by enhancing expert governance and by bypassing democratic procedures, which increases the problems discussed at the conference. On the other hand, the EU generated new forms of citizen participation, yet the question is in how far they remedy the legitimacy problems.

Finally, Claudia Wiesner asked the panel discussants to each present a short statement on the question whether politicisation could be a solution or an obstacle to the discussed problems?

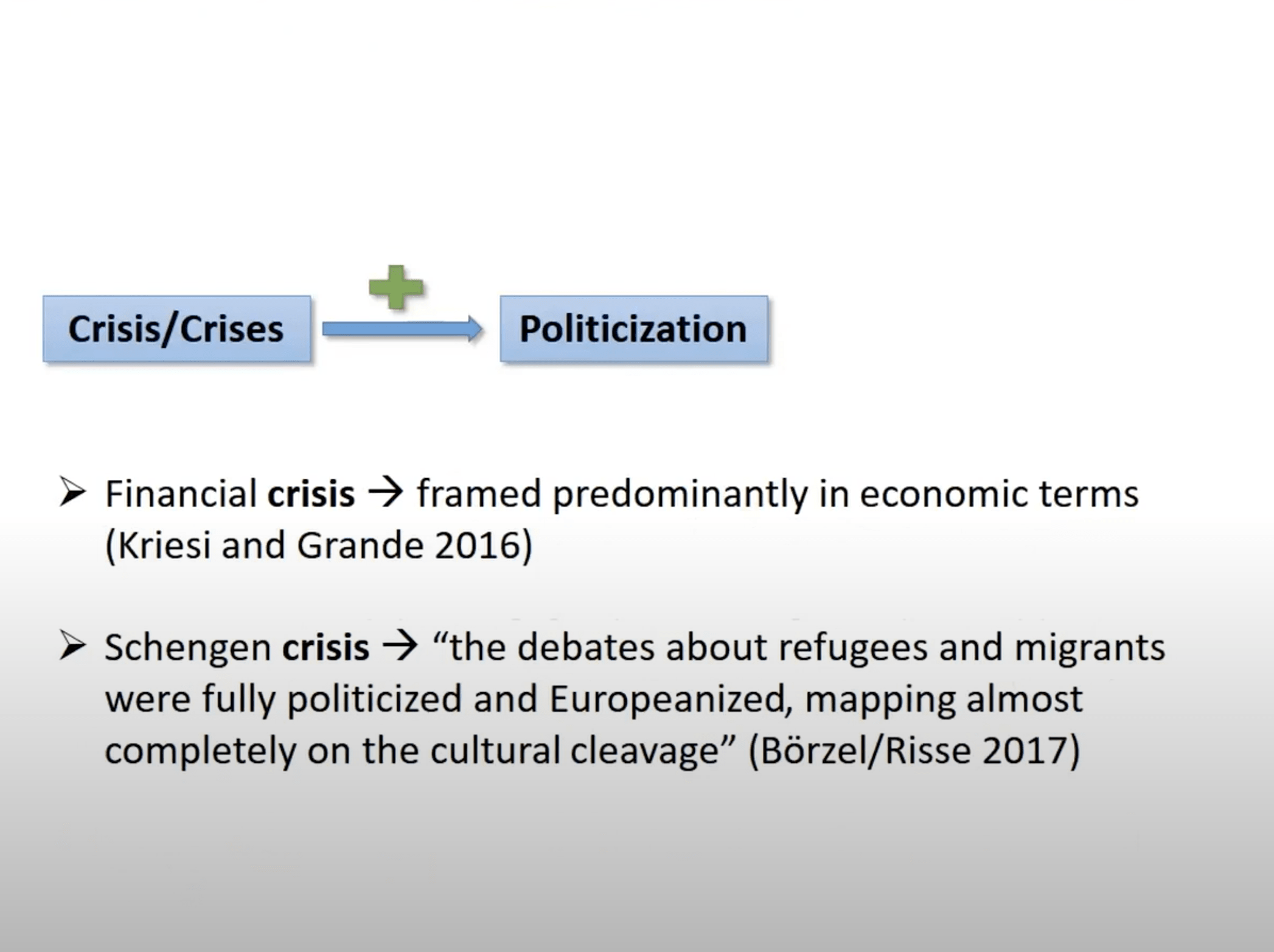

Lisa Anders initiated the debate. In her statement, she set up the hypothesis that on the one hand crisis enhanced or boosted EU politicisation and led to integration, and on the other hand, politcisation triggers crises within the EU integration process.

Anders described that EU integration was furthered through politicization processes triggered by crisis. These politicisations, however, she noted, should not be understood as an automatic response, but as an actor and party driven process. Moreover, different crises lead to different forms of politicisation.

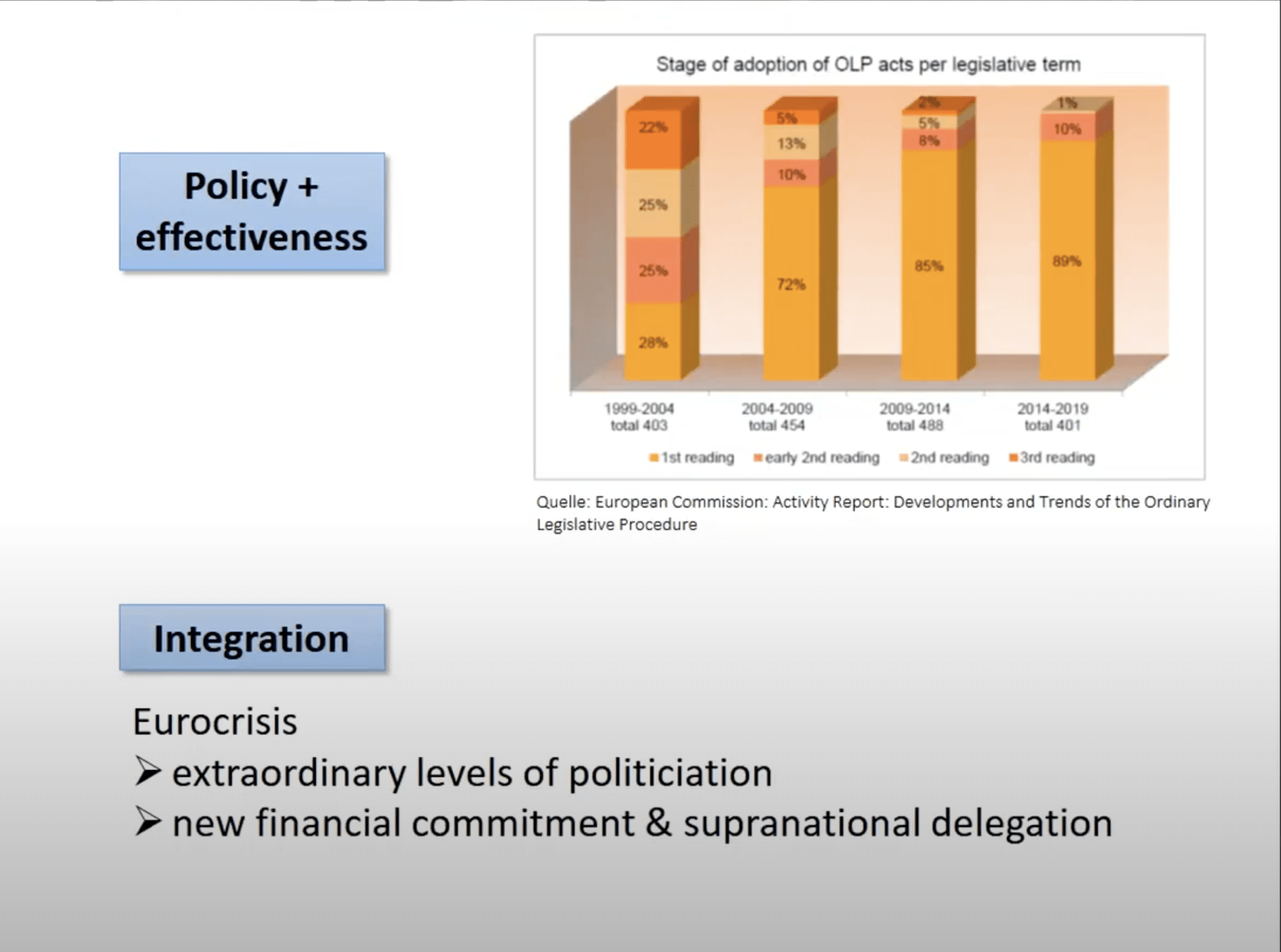

With regard to the second part of her hypothesis, Anders claimed that we can expect politicisation to enhance democracy as it potentially tightens links between citizens and their representatives, yet the downside for EU integration is that it also tightens the hands of representatives (because they are responsible to citizens). This means that compromise on the EU level is harder to achieve. Thus, depoliticisation becomes crucial on the level of the EU – in fact the EU administration took up opportunities to shield decision from public scrutiny, diffuse public responsibility, engage in blame avoidance and arena shifting strategies. In sum, Anders said, politicisation can culminate in a policy or effectiveness crisis or in an integration crisis. However, empirical research so far shows that a high level of politicisation neither led to policy crises nor slowed integration. Crisis led to politicisation, but politicisation does not necessarily entail new crisis and did not lead to an end of EU integration so far.

The next discussant Luis Bouza opened his statement with the prophecy that politicisation is here to stay within the European Union. Yet, he claimed that we need to differentiate between different forms of politicisation as well as different forms of crisis. Politicisation on the EU-level means something different than politicisation on the national level. He confirmed that politicisation is not automatic, but a result of political initiatives, it can be driven by national or transnational actors. Bouza described Emmanuel Macron as an interesting figure: on the one hand, he is a neoliberal, on the other hand, he counteracts the tendency of neoliberals to depoliticise the EU and politicises EU affairs. Politicisation and technocratisation are not the only alternatives. We can observe politicisation (ex. Spitzenkandidaten procedure), but we can also observe a shift in technocracy, technopopulism and politicisations which trust in technocratic solutions.

Philip Liste described politicisation as the introduction of political contingency, it is the opposite to „tina“-Politics („There Is No Alternative“). According to Liste the modern State has always limited contingency, i.e. depoliticised. Under modern conditions, he argued, politicisation and de-politicisation are in a dialectical relationship and crisis is to be understood as a moment in which this relation comes to an end. So, one faces a crisis if a system no longer works or if those involved in the system do not want the system to continue to work.

If the system were the EU, i.e. determined by legal and administrative functions, this would mean that these legal and administrative functions would be called into question. The system then either could react with reform, or there is a revolution. That would be forms of politicization. There is, however, a third option, the counterrevolution, or what is often referred to as a state of emergency. This is another way of removing the limitations imposed by law. Politicization is always partial, whether it is rated as good depends on the perspective. EU regulation, for example, has advantages for some and disadvantages for others. A strong EU is not good for everyone.

The last discussant Meike Schmidt-Gleim, continued the discussion by claiming that politicisation is neither negative nor positive by itself. She confirmed the position of the precedent discussant that politicisation is about opening up alternatives, about making the fundamental contingency of the present status quo visible, and she claimed that the outcome of politicisation depends on how something is politicised, on what is the hegemonic discourse of politicisation. Therefore, she proposed to ask why the reputation of politicisation within the EU is so negatively connotated in many contributions? She claimed that low voter turn-outs of the EU election are not due to politicisation, but due to a too ‘depoliticised public’ – depoliticized not in the sense that the subject matters are not politically discussed within the EU context, but in a sense that the EU did not generate sufficient identification of its subjects as EU-citizens: EU-sceptical politicisation is due to the failed construction of a European demos, of a common public, of a common interest. Instead of becoming a part of the ‘us’, the EU became the other of these citizens, ‘us’, the people against ‘them’ the EU.

After her intervention, Schmidt-Gleim noted that during the previous two days there had been a lot of talk about the ambiguous fact that the concept of crisis was being used in an inflationary way and at the same time that something actually was at stake. She said it would be interesting to find out how the two perspectives mentioned are related to each other and how the inflationary crisis tries to blind society from the real crisis or whether the inflationary crisis is part of the “real” crisis.

Claudia Wiesner then initiated the second discussion round, in which the four podium guests were able to comment on the statements made by the other participants in the discussion.

Lisa Anders stated that academics should take a closer look at what guides politicisation.

Luis Bouza explained the increase in the European Parliament’s electoral turnover in the last election in 2019 with the fact that voters realised that something was at stake.

Philip Liste referred to Meike Schmidt-Gleim‘s lecture and said that there are different views of what the European Union should represent.

The discussion was then opened to questions and comments from all viewers. Elena García Guitián, Uli Brücker, Niilo Kauppi, Christian Schmidt-Wellenburg, Meike Schmidt-Gleims and Ana Matan discussed, among other things, participation in European elections.

The conference concluded with a final round of comments from the panelists. Meike Schmidt-Gleim stated that the topic raised will only be the beginning of a long discussion. Philip Liste added that more efforts need to be made to find answers to the question where the crisis is located in the first place. Luis Bouza asked to what extent politicisation was a social fact and Lisa Anders stated that there was still some work to be done to precisely define the topic to be discussed. Claudia Wiesner ended the conference with these summarizing words.

Tagungsbericht